This is a collection of writings by my father Australian artist Peter Benjamin Graham 1925-1987. Some passages are taken from autobiographical notes, others from letters and essays. Most of his paintings are stored in my garage and despite a valiant attempt to promote his work over the years, my family no longer have the time or energy to do more than share it on line. I am creating a comprehensive catalogue for posterity, and so am interested to here from anyone who may own one of his pictures so as to include it in this document.

Euan Graham

CHAPTER 1 – ‘PETER WILL BE AN ARTIST’

Art histories are many and varied. Some deal with artist, some with places, some with ideas. Perhaps memories are not a good basis for art history, even a personal one such as this. The tendency for the neat anecedote that conveys a personal prejudice is always a trap for the autobiographer, especially when the odd chip on the shoulder can still become a wood pile of disappointed hopes. The history of any artist is possibly a history of ambition, to be as good as – to be ‘up there with them’, to be a ‘great’ artist, to innovate a new art form, to add a significant chapter to the history of art – recognition, fame, fortune. But this, of course, is all subject to the whole process of life and that sometimes … of learning. ‘Learning by doing’ is an oft-quoted phrase, but the whole process is so complex that the awareness of what is happening to oneself is often lost and discovered a thousand times as the course is influenced by the equally numerous changes that take place within and [outside] oneself.

To begin with the first drawing is a kind of nonsense that is repeated in families and becomes lore for doting aunts and uncles and cousins. Unfortunately, the first drawing is what the visual artist is about. The craving for that first communication success can be a driving force that never lessens throughout an artist’s life, even long after the child has ceased to ask, ‘What will I draw now, Mum?’ and the adult sees the solution to yet another idea as a web of lines that capture meaning.

The desire to succeed as an artist was implanted very deeply and very early. I began school at Hartwell State School in l930… In the first week, I did a drawing on my slate of wheat stooks and a post and rail fence. This caused quite a stir [and] was the first time it was said, “Peter will be an artist’, a traumatic intrusion on the tender sensibilities of four and a half years that was to shape my whole life. The teacher took my slate away to show someone else and not knowing what to do, I waited. My sister went home for lunch without me and many tears and much anguish occurred – and that is how I began.

My father gave me my first lesson in drawing when I was four – how to draw a boat. I did not understand why it was drawn as he showed me, but I observed that his way was better than mine and so I imitated what I saw. He had learned to paint and to make violins from a German immigrant in about l898. My father also taught me to play the violin. This was his grand passion which he pursued all his life from about eighteen, both [violin] making and playing; to discover the secret of Stradivarius, his holy grail. I can still play the violin at about aged seven level and read music with great difficulty.

Two fairly happy years at Central School were mainly hampered by the ghosts of jobs and when at the end of the year, most of the boys sat for, and entered Melbourne High School, I was encouraged by the drawing teacher, a Mr McCubbin and nephew of the artist of the same name, to go to Melbourne Technical College Art School, my marks for geometry and art being very high. I was interviewed by the head of the college, Mr Brown, and teacher Vic Greenhalgh, a sculptor, and was offered a free place at the art school for one year, worth the princely sum of about fourteen pounds. My father allowed me to accept it providing that I also studied a related trade. (In the early 30s in Australia, art was not seen as a desirable vocation – specially in a lower middle class environment that was one step removed from small dairy farming on one side and … mining gold and minerals on the other.) I selected lithography, and as they did not teach this as a subject during the day, I was to attend as an independent student at the apprenticeship night classes.

To draw and paint every day all day for a year! I was in a euphoria of a kind that I’ve experienced only a few times in my life. Everything was experienced in a haze of dreamlike continuity. I was taught art appreciation and lettering by Mr Ferguson and Mr Jenkin; drawing from plaster casts by Miss Montgomery; pen-and-ink illustration by Mr Moore and design by Murray Griffin, spending my lunch hours in the National Gallery.

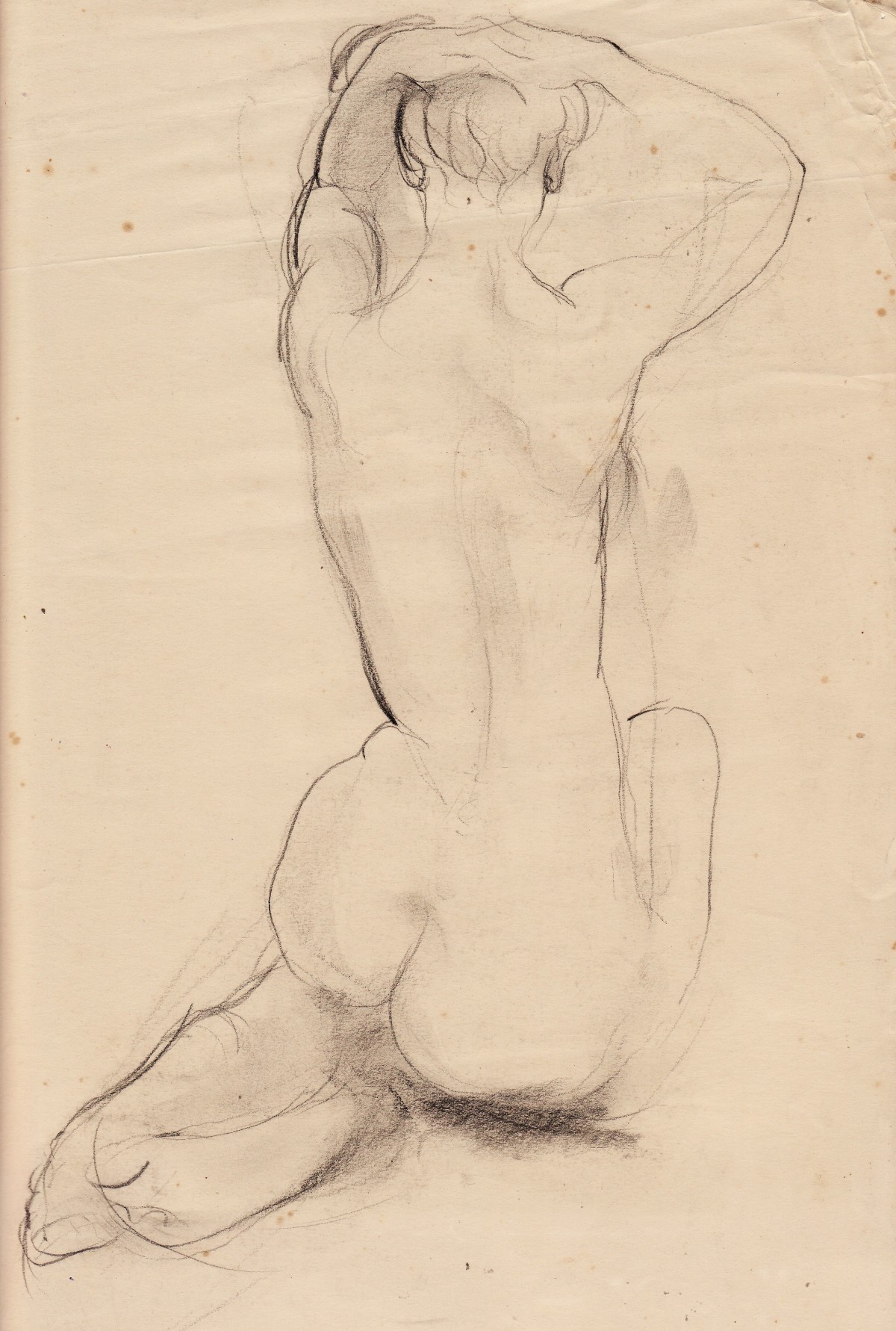

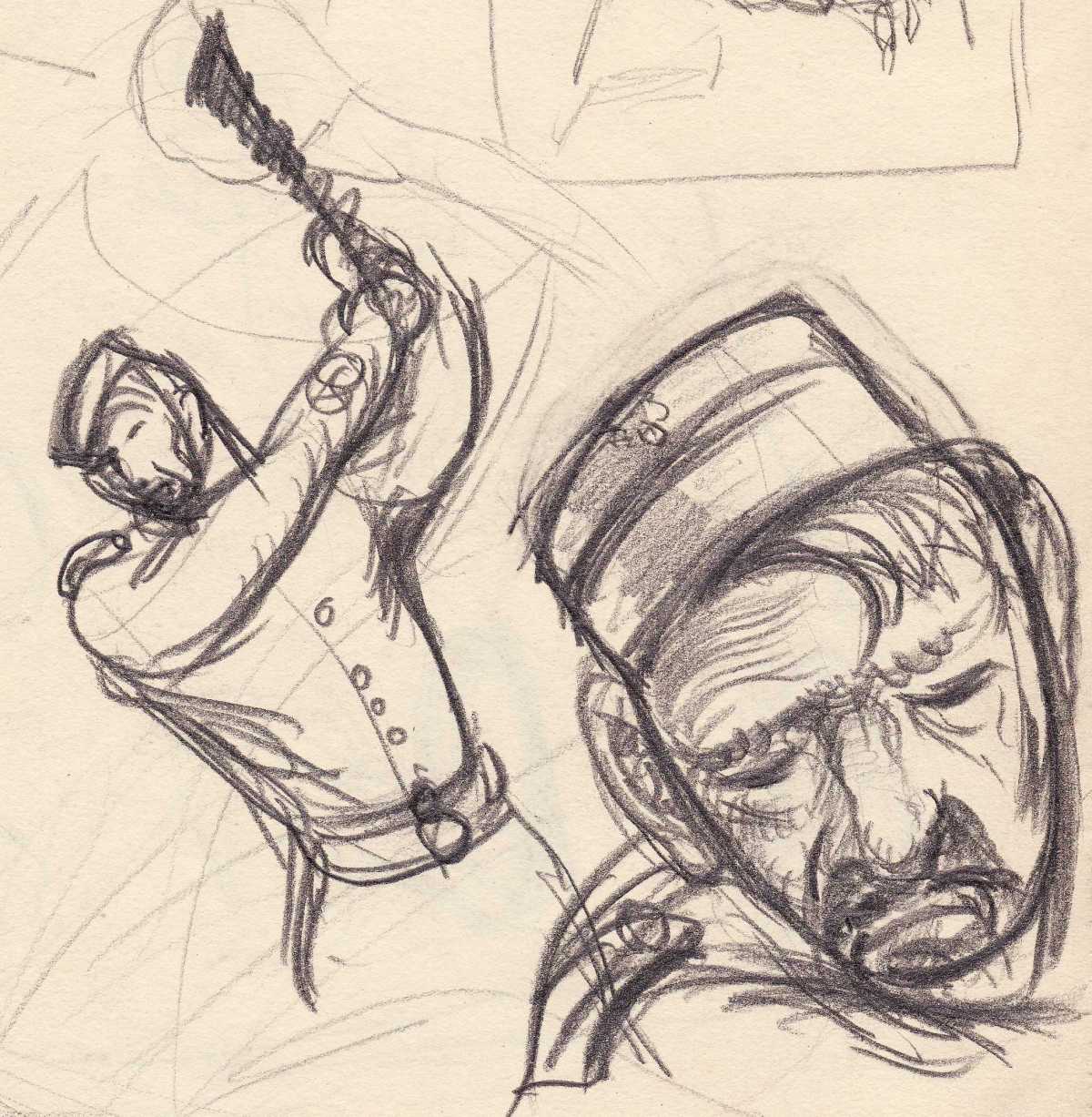

At the end of what could only be called a year of absolute bliss, I failed to win the coveted scholarship for a complete course at the art school and began work with Harold Ross, a freelance hand-lithographer who taught at the college. He introduced me to many printing houses and a wide range of people associated with the slowly-dying hand lithography trade. Urged by many of the older men, I became apprenticed to the ‘new’ photo process at Photogravures Pty Ltd where I spent the whole of the wartime seconded to the making of security documents for the war effort. Under Harry Falla, I began to learn all phases of the photogravure process – a copper plate intaglio method of printing – in the only trade house then active in Australia. This trade was not taught in any of the schools at the time, but my appetite for studying fine art had been whetted, so I enrolled for figure and head from life classes at the Melbourne Technical College under Vic Greenhalgh, and continued my lithographic studies with Harold Ross. The following year, l942, while continuing my apprenticeship with Photogravures, I studied in evening classes with John Rowell, who was considered the best teacher at that time and with whom I continued to study until the end of l945. The desire to be an artist was still the major driving force and this was responsible for the constant night school of four nights a week study.

Many years have passed since the hopeful student and aspiring artist equipped with charcoal stick, Michelet sheet and slice of bread, mounted sheet on drawing board to do battle with the mysteries of light and shade. To those uninitiated into the art of smudge and rub, the slice of bread was not to sustain the combatant in this great confrontation, but used, by diligent kneading of pieces between the fingers, to form an eraser of error, or to create a highlight, as the fortunes of the encounter progressed. If you were a humble beginner, you did battle with the strangely-dismembered fragments of human physiognomy: ears, noses, eyes, all cast when new, in gleaming white plaster, in a scale much larger than life. And when a senior, mecca of all achievement – the life class.

I was born the second child of Henrietta and Ben Graham on 4 June, l925 at Burwood district Hospital in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. A sister, Mary, is two years older and another sister, Ruth, four years younger. My home in Hartwell was built by my father as he was at this time, a solid plasterer who contracted work through the State Savings Bank (Bank Houses) and his connection with a number of local builders. My mother’s family, [the Mitchells], came from Heathcote [in Central Victoria] where they were a most respected and respectable group and were frequent visitors to my parents’ home. My mother was the eldest in a family of five girls and two boys and is still alive. She will be ninety years of age this year [l987]. My father was ten years older and died at the age of ninety-five in l982. When he was six, his father was killed in a train accident and while his mother and relatives lived in our street, Lodge Road, Hartwell, they did not have a great deal to do with each other. The memories of my maternal grandparents are far greater. According to my mother, her father, Fred Mitchell was a ‘clever, lazy man’. My mother still says with pride that her father went to the Bendigo School of Mines till he was eighteen, and was always reading. He had about him something of the period of Edison where everyone hoped, with a little knowledge, to produce the great invention of the age and of course, the fortune which was assumed to follow. He did neither of these things but he did run the local motion pictures in the fire brigade hall ( from silent movies to the first talkies) and had the distinction of obtaining one of the first twenty-five licences to run motion pictures in Australia, along with a gold-buyer’s licence, a steam engine driver’s ticket, and a caylian clay pit that gave him a regular, though modest income. Needless to say, he did not dig the clay, but employed a man by the wonderful name of ‘Carboon’ to horse and dray the aforesaid clay to awaiting railyard trucks. I went [to Heathcote] often as a child in school holidays. The early memories of kerosene lamps and candles and the Edison gramophone with long celuloid funnel are as strong as those of suburbia where electric light and the crystal set [wireless] were the symbols of modern Melbourne.

Perhaps it is this small-town aspect of my background that established a central core of regional identification – at least it stems from that. Regionalism is a compound of many things that condition the senses and the young perception of place and identity can have a lasting effect. My first efforts at pictorial composition used the perception of social conditions as a starting point. My more general idea of region and its place in the formation of art ideas began around l945 during the war, when I was just starting to paint. Through my trade I met the lithographer, Rembrandt McClintock who introduced me to the Melbourne social realists Frank Andrew, Ma Mahood, Vic O’Connor, Josl Bergner and Noel Counihan in the early ’40s. I began painting and exhibiting as a social realist, helping to paint banners for May Day marches and joined the Victorian Artists’ Society.

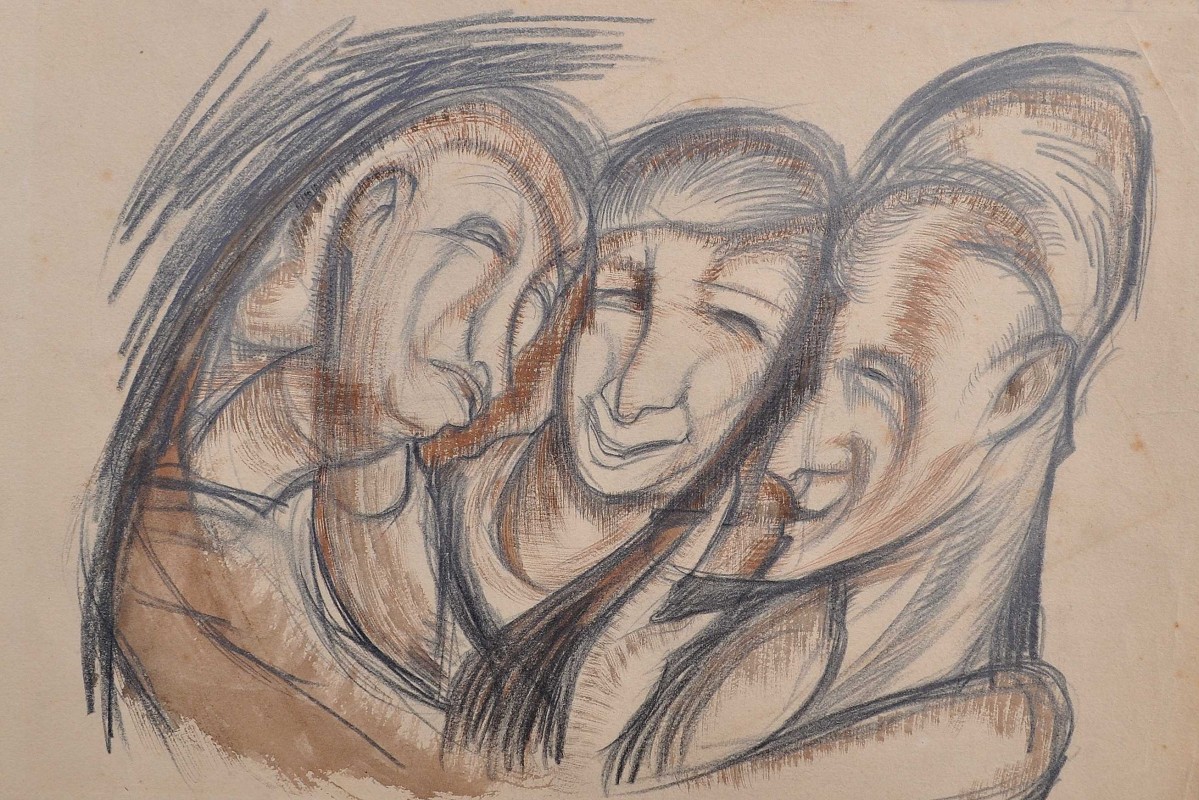

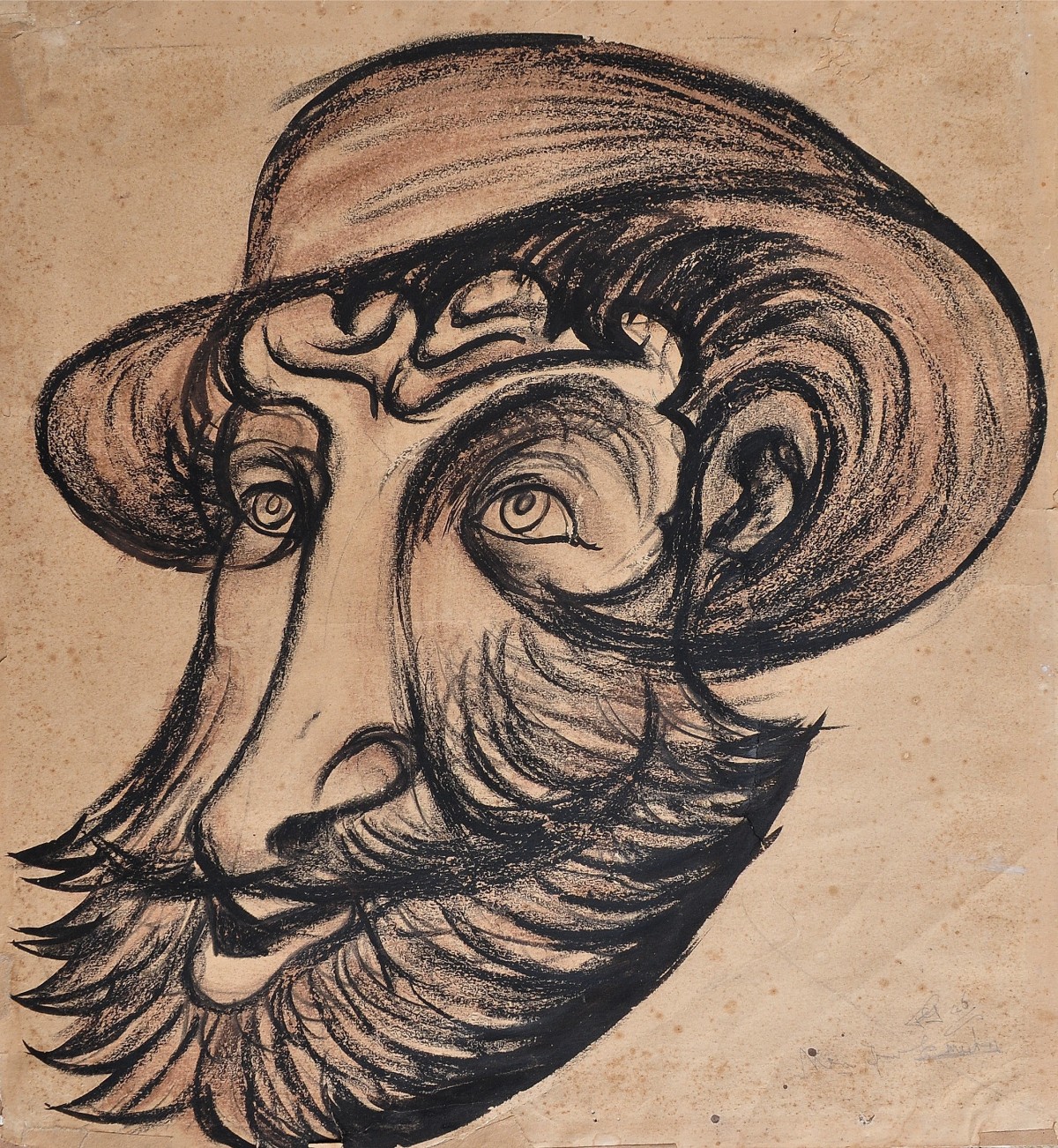

![1946_019-[H035]](https://peterbgrahamcom.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/1946_019-h035.jpg?w=1200)

Extract From Letter to Bob Calwell 23/5/45

Hello Bob,

…Don’t think I’ve been working hard because I haven’t. I spend hours (or it seems like hours) just sitting looking and thinking, trying to figure it all out and my latest conclusion is that if I paint anything at all I must be familiar with it. Therefore I am painting the front street, the side street, the back lane, anything that I really know so – and now I come to the important point, that is to you. You are in Tasmania away from home, feeling indifferent about any family affairs. You are fortunate in all these things if you can utilise these factors.

If you are genuinely affected by your surroundings and your technical ability of a reasonable standard, you can express that feeling of which you speak, but too many people, artists, are affected not by the feeling and surroundings, but with other people’s views on these things – and there is the reason for empty paintings with no meaning other than a technique enclosed in a frame.

If I were a preacher and giving a sermon to young artists students I would say ‘Don’t be afraid of ridicule, take your means, consolidate them, use them sincerely as did Van Gogh and your result will be art itself.’ If only I could practise even a small part of that which I think and try to preach, I would not be satisfied, but still strive after greater perfection, in expression and sincerity of living and expressing living, for this is life itself and can never be.

What-Ho Bob

…I feel as if the biggest change in my education, that is my art education, is at hand. The things that make art not just a by-product in life, but life itself: creation, within the grasp of a poor human; self-expression with art as its realisation. This feeling which I cannot express fully, a kind of bigness inside you that must come out and when it does, must be controlled to just the right extent so that this expression is not overpowered by technical difficulties.

I’ve painted a picture for the Australia at War show but I don’t think I’ll be able to get it in in time… The title is Friday Evening on the Home Front and if that ain’t clear well it’s a painting of…people buying tickets at one of these ‘ere spinning jinny affairs to try and win the beautiful doll. In the foreground is an animal’s head, and a collection box held by a beautiful damsel…. a study in mass and design or something – anyway that’s what I kid myself… I did put some thought into this painting and would very much like to have it in this show, but as Frank Andrew said, I might be able to get it in at the end of August and that’s in three days time [but] I’ve got to paint the frame again. I’ll be running pretty close on the limit – ah well, here’s hoping. I bought an old frame – one of these heavy gilt affairs and gave it a coat of flat white for the doings. I only hope it isn’t looked at too closely. [Ed. note: Friday Evening on the Homefront was exhibited in the Australia at War competition at the National Gallery of Victoria, and was favourably mentioned by the art critic of The Age , George Bell.]

Grahame King and I got together one night a little while back up at his studio and tore one another’s work to pieces (like hell) – take this as meaning what you like. Had a really good evening and learnt quite a lot, also verified a lot of my own ideas. There’s nothing like that occasionally, even if it does make you think you’re pretty good or very inferior (after thought).

Here’s another little thing in water colour only a little painting about 10″ x 12″. I call it A street corner at night. It’s got some quite fair colour in it. It’s one of the “horrible” modern type pictures. I judge it one of my best as yet. Of course I have to admit that that’s what Grahame King said when he saw it. I’m going to have it framed then, to shock Mr Rowell with it (I hope). I’m painting more in pattern now as you see; also thinking more of designs and of two-dimensional and three-dimensional painting. But I’ll tell you all about that when I see you, hoping it won’t be long.

Pete. G.

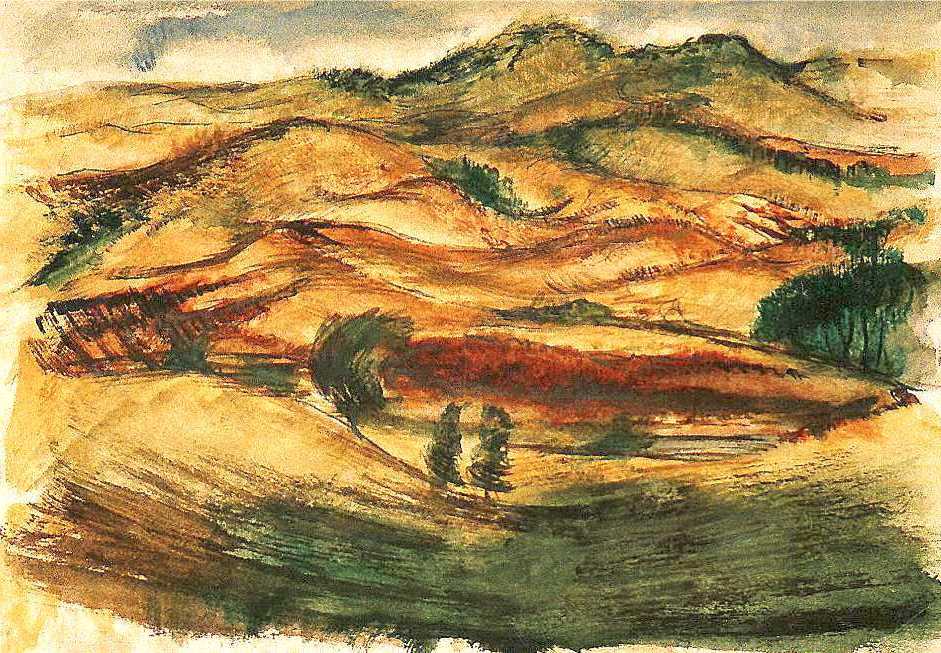

That year 1945 I was runner-up in the Ferntree Gully watercolour prize with Queen’s Bridge, and I won the next year with Back streets, Hawthorn. This was criticised by Melbourne art critic, J.S. MacDonald, who likened it to a Warsaw ghetto. This was a reference, perhaps, to my association with Josl Bergner, the Polish artist.

Letter from Noel Counihan, December l0, l946.

Dear Peter,

Just a note to congratulate you on your Ferntree Gully success. It gave me great pleasure to read of it. In fact it gave me as much pleasure as it enraged that bitter old fascist MacDonald. It was your bold realistic watercolour which drew the chauvinist taunt of “Poland” from the decrepit old reactionary. The better and the more realistic your work becomes the more you will wound and annoy the enemies of the people. I was also very pleased about Grahame’s success [King], and only disappointed that he had to share both the honor and the ‘dough’ with a mediocre painter like Alan Moore. Moore isn’t a bad lad from what I’ve seen of him but as an artist I fear he’s pretty dull and in need of vast injections of a scientific, materialist philosophy.

Grahame’s interest in “Labor” as theme for his painting is a splendidly healthy sign and augurs well for his progress. He is very self-critical too, and that’s a necessary quality in an artist.

I would like to see more of your new work. Perhaps Vic, Josl and myself could come to see you one evening soon or in the new year, if you can spare the time?

Yours fraternally,

Noel C.

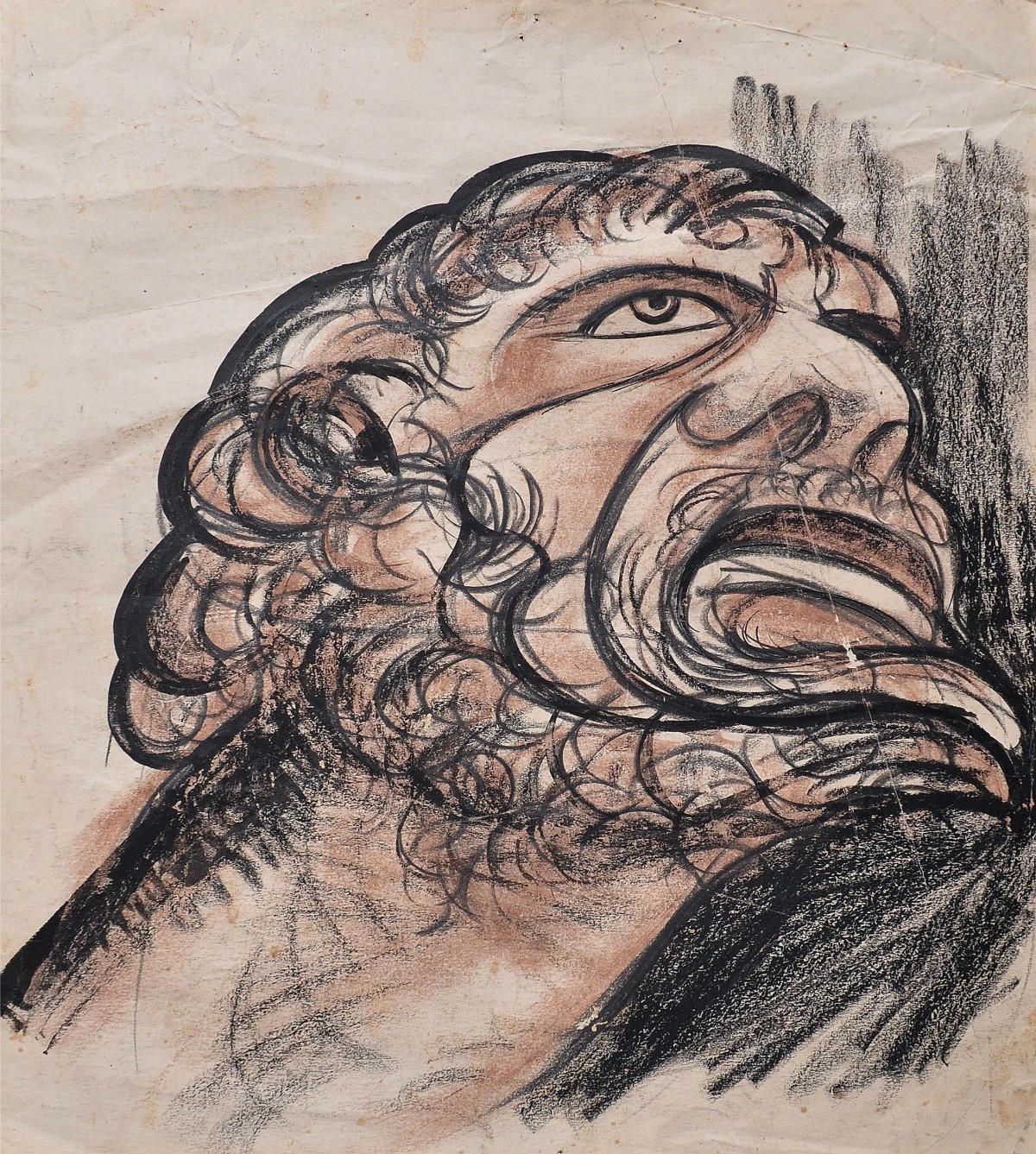

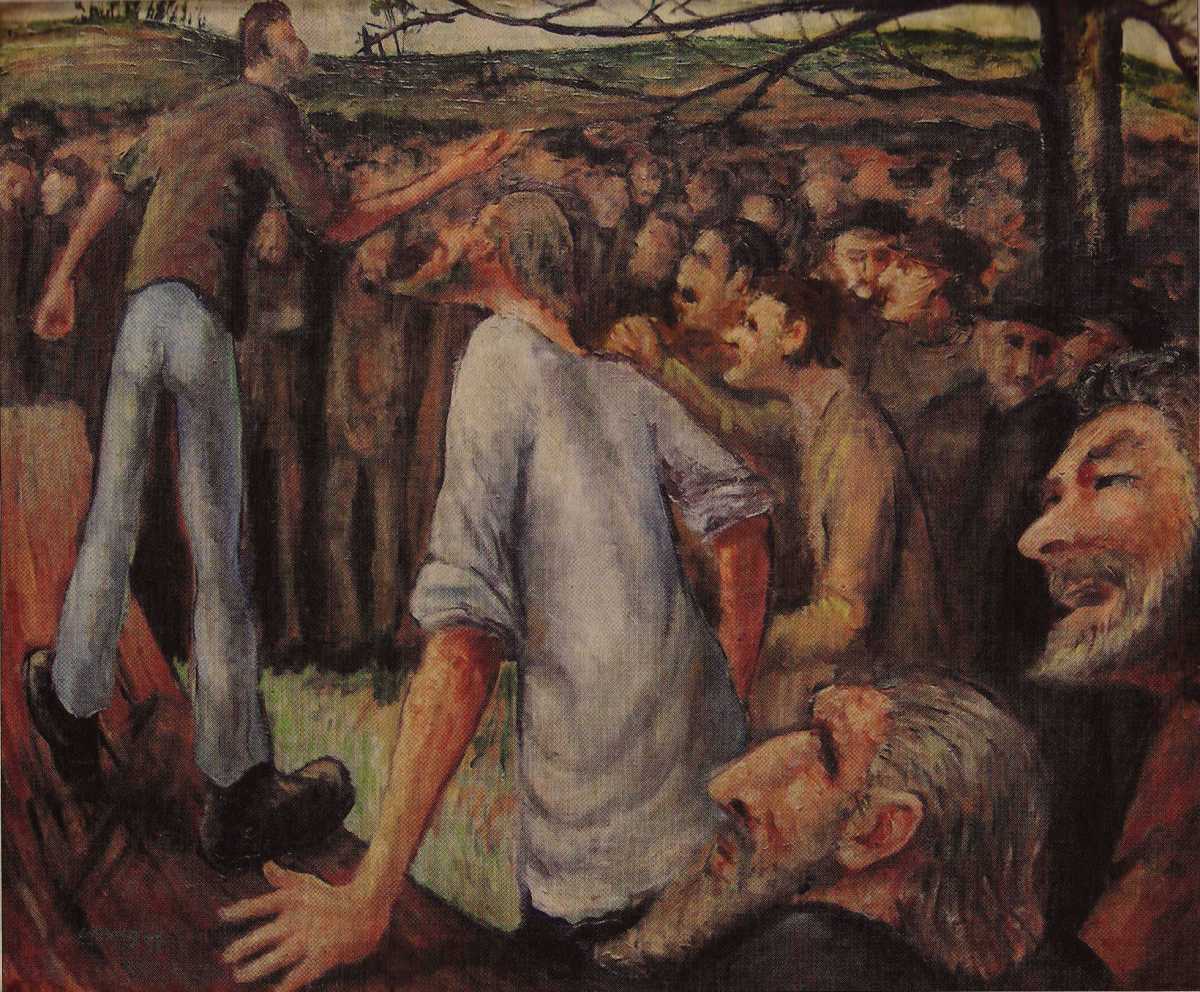

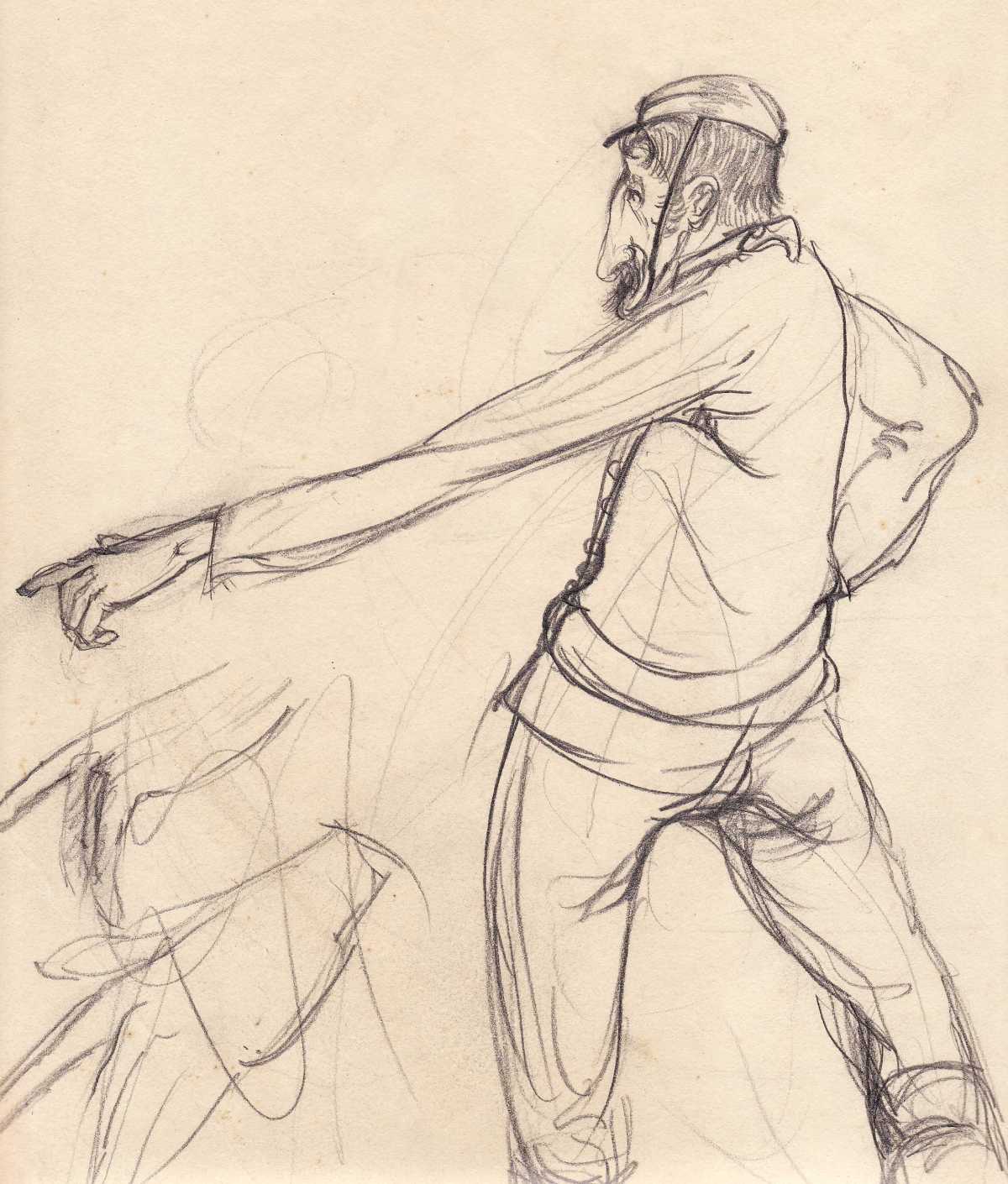

In fact, Back Streets Hawthorn was based more on the technique of the American, Birchfield, whose large watercolours continued to interest me for at this time, I met several American servicemen at the College, who introduced me to the first of many influences that were to shape my art – the American regional painters. Foremost amongst them were Thomas Hart Benton and Charles Birchfield and the social realists Rico Lebrun and Jack Levine. At the time, I was finding it difficult to approach contemporary subject matter and sought ideas in historical events of a political nature. Peter Lalor addressing the miners before Eureka was painted at this time. It was influenced by Hart Benton’s kind of long-angled perspectives and distortions, taking a low angle of view and combining it with a level view of the same subject plane. It was the second in a group of paintings, the first being The Burning of Bentley’s Pub. It was followed in l946 by a huge work known now as The Convicts but reviewed when shown at the Victorian Artists’ Society as Historic Parallel.

The end of the war saw an influx of discharged servicemen (rehab. students) to the College which transformed the environment dramatically. The battle lines between ‘modern’ and ‘academic’ art were drawn. The Meldrumites, the Contemporary Arts Society, the George Bell faction, the Angry Penguins and social realists v. the old conservatives (MacDonald, D. Lindsay and Buckmaster) created an environment of conflict of which I was not completely aware being of a rather innocent nature. But the conflict was not only between conservatives and progressives but within the radicals themselves. Although I read Adrian Lawler’s Arquebus at this time, I was still not really capable of grasping the outline of the conflict which was quite bitter and shaped much of the art at the time. All were vying to try and sway the artist towards their way of thinking. You either drifted towards one or the other; and in my case, I drifted towards the social realists; but not entirely, because I also wanted to paint landscape as I could see landscape was still a very big part of Australian cultural expression. I didn’t think of it in those sophisticated terms – it wasn’t as clearcut as that – I just thought of it in romantic terms of a person doing it in that environment.

I met Grahame King at this time, who had a similar background in lithography as well as gallery school training. On discharge from the army, he became secretary of the Victorian Artists’ Society. This body had long been the bastion of the neo-academic movements, but with King’s leadership, and the influx of new members, it took on a new role in the propagation of the modern art movement. While the heavy conspiratorial nature of the social realists attracted and was an exciting atmosphere, my grasp of politics and its relationship to art was ingenuous. The arguments for and against art for art’s sake and art in the service of propaganda were issues not easily resolved and it was with relief that I began to move with Grahame King and Douglas Green, another rehab. student at the National Gallery. At the time I was the proud owner of an old Chevrolet. As its hood was torn, I lined it with one of my paintings and with this means of transport we three set up an artists’ camp at Flowerdale in a kind of emulation of the Heidelberg School days. Another associate at this time was the war artist, Max Newton and it was during these days that the idea of going overseas and seeing some real art originated.

The beginning of l947 and the decision to accompany Grahame King to England was made. Before I left, an oil painting Smoko in Hardware Street , my first major attempt at a contemporary subject for some time, was completed and I also won The Herald drawing prize with a work entitled The Smokers. This completed the first phase of my development.